Introduction

In my map-making work, there are two recurring words that serve as cornerstones: the first is ‘landscape’, which we will explore in more detail on the almost eponymous page (and the equivalent ones published in the Barolo section); the second is ‘context’, which should even precede it in importance.

Context can be of various types.

In our case, it is mainly a geographical context, which in turn can be very broad, as well as limited.

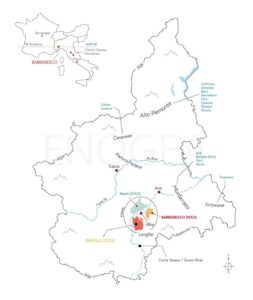

Starting from the first, and more precisely from the two maps below, we can say that the Barbaresco area is located in the north-western part of Italy and more precisely in southern Piedmont. To the south we have the Apennines, while to the west and north we have the Alps, which together contribute to shaping the climate of much of Piedmont.

Taking the Po as a reference point, which flows through the centre of the Pinaura Padana, to the north we have the viticultural areas of Alto Piemonte – where Nebbiolo is the dominant grape – and Canavese, both characterised by a cooler climate and, on average, more rainfall. South of the same river, the first wine-growing area to be encountered is Monferrato, characterised by gentler hills and a warmer climate – particularly north of the city of Asti – while the altitudes gradually increase moving southwards towards the Apennines. Barbera is a ubiquitous grape variety, to which Moscato (Asti and Moscato d’Asti) is equally important in the southern part of Monferrato.

Last, but not least, is the area known as Albese, i.e. everything that gravitates around the city of Alba and within which we can make further distinctions.

Taking the Tanaro river as a reference, which flows from the south towards Asti, this area can be divided into two macro-areas. Roero, to the north, is characterised by more recent marine deposits (Pliocene), a slightly warmer climate and an ampelographic offer that focuses essentially on three grape varieties: arneis for the whites, barbera and nebbiolo for the reds.

South of the Tanaro river we find the Langhe, of which Barolo and Barbaresco cover only a minority part. In fact, the Langhe region borders Monferrato to the east and almost brushes the border with Liguria to the south, thus including part of the Asti and Moscato d’Asti appellations, and the entire Dogliani area, where the dolcetto grape variety dominates unchallenged.

In comparison with the Roero, Barolo and Barbaresco have, on average, a cooler and more breezy climate, but not as cool and rainy as that of Alto Piemonte and Canavese. From a geological point of view, as we will see on the page dedicated to this subject, the origin is also marine, but older than in the Roero, while the grape variety of reference, at least if we are talking about Barolo and Barbaresco, is Nebbiolo.

To sum up: if in a broader context the cardinal points are the Alps, the Apennines, the Po river, the Alto Piemonte and Monferrato, in a local context the geographical and above all the visual references are, in order of importance: the Tanaro Valley, the Roero, Alba, La Morra (which identifies the Barolo area), Monviso and finally Alta Langa. These are real ‘cardinal points’, all clearly visible in the first of the two panoramic images.

A final note on the spelling. Langhe and Langa are two words that identify the same area: the first is the one commonly used in Italian, the second is instead of more local use and should not be confused with the name Alta Langa, whose production area also includes part of Monferrato.

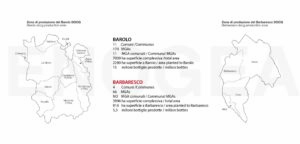

As for the production context, the image below, comparing the Barolo and Barbaresco appellations, is both useful and self-explanatory.